Vidrala: Message in the bottle

Part 1: A primer on the European Glass Packaging business & its corporate history

Welcome to the Staying Rational newsletter, where I analyze companies that are from the “old” economy and without much hype. To my eyes, these companies are interesting either because they are too cheap to ignore — such as Ibersol — or because the market doesn’t seem to fully appreciate their quality as long-term investments, like Vidrala.

Let me start with a story told by Morgan House here

This guy – we’ll call him Jim (not his real name) – was driving around Omaha with Buffett in late 2009. The global economy was crippled at this point, and Omaha was no exception. Stores were closed, businesses were boarded up.

Jim said to Warren, “It’s so bad right now. How does the economy ever bounce back from this?”

Warren said, “Jim, do you know what the best-selling candy bar was in 1962?”

“No.” Jim said.

“Snickers,” said Warren.

“And do you know what the best-selling candy bar is today?” Warren said.

“No,” said Jim.

“Snickers,” said Warren.

Then silence. That was the end of the conversation.

I think what Buffett meant was: Focusing on what’s never going to change is more important than trying to anticipate how something might change.

While a lot of things are uncertain in the world, humankind’s preference for glass packaging is one that I think is very likely to hold true for a long time. Glass has been used for thousands of years, historians believe the first glass bottles were made in 1500BC. A quick history recap can be found here — I thought it was pretty cool that glass bottles were once shaped by a man physically blowing into a pipe. We came a long way since then and invented much cheaper packaging such as paper and plastic but glass maintained its relevance to this day.

From beverages to food, glass is frequently the preferred container. It’s associated with quality and it is perceived to be environmental friendly since it can be recycled infinite times while maintaining its characteristics. Glass containers have also become a core part of brand identification.

Besides secular demand stability, the glass packaging industry also benefits from other characteristics that make it an above average business, allowing for most players to enjoy higher returns than average.

Local oligopoly with limited competition from abroad

Local sales = local oligopolies: Glass containers (hollow and heavy) are expensive to transport. High sales density is key: a large number of volumes must be sold within 500km of the production site in order for it to be economically viable. Most sites are either close to where the product is produced or where it is consumed. Some regulations also reinforce these local dynamics. For example, the wine produced in Iberia, France and Italy is mostly from DOC regions (designation of controlled origin) and therefore must be produced and bottled within the region.

Local scale and high utilization is paramount to dilute fixed costs

To understand how utilization impacts glass producers’ profitability and their ability to finance capex, I will use two charts from an old Vidrala presentation.

Because there was excess production capacity back in 2010, Vidrala was operating only at a level of 85% (vs. close to 100% today). In that presentation, the company points out what EBIT margins it would be able to achieve in case it operated at higher capacity levels. If the chart scale is to be trusted, we can infer from the chart below that going from 85% utilization to full capacity (85%+15%) would increase EBIT margin from 16.2% towards 20+%.

On the second chart we can see that there is an even more significant impact on the company’s ability to finance its maintenance capex with organic cash flow:

There are also typically higher initial set-up costs for the initial furnace than on the additional ones: Accordingly to Verallia prospectus (Oct’19), a greenfield plant with an annual capacity of 80kTons (with one furnace) would cost >€80m (ie >€1m per 1kTon), whereas the cost of additional furnaces can be significantly lower. Verallia’s new furnace in Brazil was half as expensive on a per Ton basis: €60m for an incremental capacity of 114kTon/year (ie €0.5m per 1kTon). So it makes more economical sense for the existing players to expand current plants with new furnaces than for a new player to enter the market with a sub-scaled plant.

The current players have also benefited from decades of industry consolidation; the top 5 increased their market share from less than 50% to ~70%, where Verallia is the current leader in Europe with 21%. My educated guess is that OI is #2 (19%), Ardagh #3 (13%), Vidrala #4 (9%) and BA Glass #5 (8%).

On the narrower sub market of Western Europe (more relevant for Vidrala) the top 4 players have now ~85% market share, up from ~40% in the 90s:

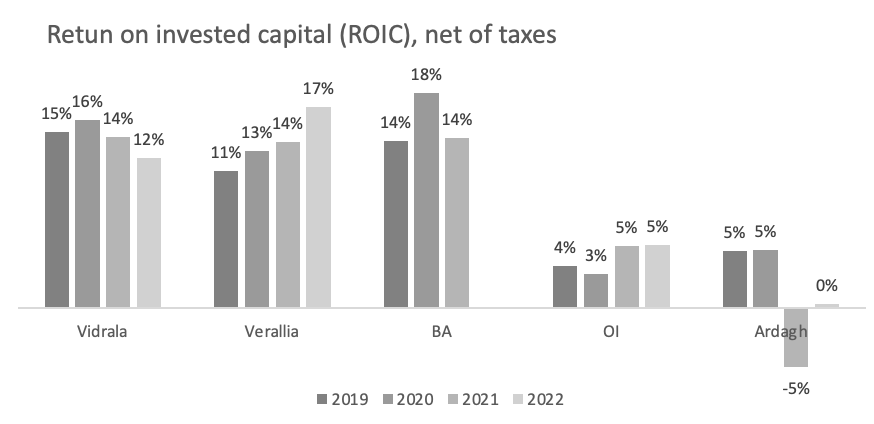

High pricing power over a fragmented client base. While the mix of clients includes both large customers (beer segment) and small ones (still wine), the overall client concentration is relatively low, leading to glass packaging producers having a strong bargaining power. Their ability to increase prices also varies with overall capacity utilization. In times when there is barely any spare capacity in the market (as 2021-23), producers’ capacity to increase prices is particularly strong. That explains why producers have been able to protect their margins despite facing significant cost inflation in 2022 due to higher energy costs (glass production is energy intensive). Verallia, for instance, has been able to keep its 2022 EBITDA mg largely unchanged helped by price increases but also by energy hedging. I believe energy hedges explain most of Verallia’s return on invested capital (ROIC) outperformance in 2022 over Vidrala (17% vs 12%).

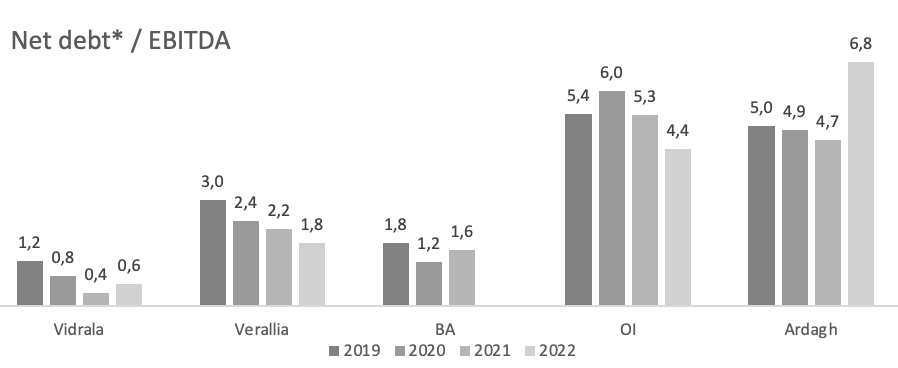

The main result of this dynamics is that most glass packaging producers enjoy high returns on capital. Well, at least the European ones do… The global players (OI and Ardagh), not so much. As I will explain later, I believe their mediocre ROICs have more to do with self-inflicting wounds and poor capital allocation decisions than with the industry itself.

Let’s now look into European glass producers with some detail including their M&A history since that partially explains the huge consolidation between 1990 and 2020.

Vidrala: Compounding machine

#4 in Europe, #1 in Iberia, and through Encirc, the #3 in the UK and sole operator in Ireland

Ricardo Gallo acquisition serves as a playbook for further M&A

Vidrala began its internalization in 2003 by purchasing a company in Portugal named Ricardo Gallo for €22m equity value, of which €4m paid in 2005 (total Enterprise Value, EV, was €72m). That marked the beginning of its internationalization and increased the company annual production by 35%. The power of compounding is well illustrated in this transaction: Unlike its other transactions, Vidrala used 500.000 of its own shares (bought in the market) to pay for a small part of this transaction (20%), corresponding to a 2.4% stake in Vidrala, worth €4.5m at the time. That initial stake has increased to 2.7% today (as Vidrala has bought-back about 10% of its own shares) and is now worth about €80m. And… it also has received €9m in dividends. That’s a 20-bagger in 20 years (>17% annual return). If you are wondering if Gallo’s family still holds this position, they actually own more than that. Their current stake is at 3.6% which leads me to believe that the family has also redeployed some of their cash proceeds into Vidrala.

Under the ownership of Vidrala, Gallo’s plant became significantly more profitable due to a combination of sales synergies (Vidrala became a more relevant player in Iberia), capacity expansion and improved efficiency.

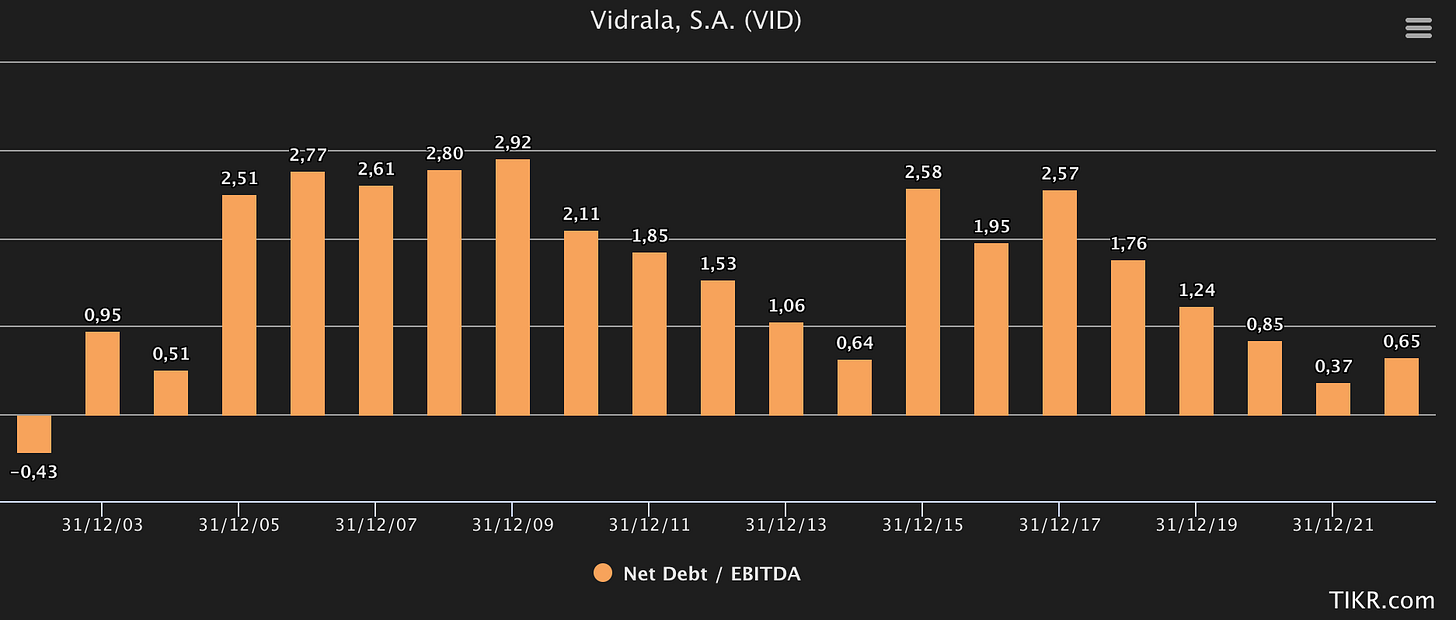

Another interesting acquisition was just one year after Gallo’s. In 2004, Vidrala bought two plants for €138m, one close to Barcelona (capacity of 195k tons) and another nearby Milan (capacity of 145k tons), when Oi Glass was forced to sell them for competition reasons. OI’s acquisition of BSN was conditional to the sale of these two plants. In just two years, Vidrala more than doubled its annual production capacity from 450k tons to almost 1m tons. All this while keeping a moderate leverage level with net debt at less than 3x EBITDA — although it certainly helped that the company was net cash before M&A.

Vidrala Net debt/EBITDA evolution (2003-22)

In 2007, Vidrala buys MD Verre (135 kton/year plant in Belgium) for €35m (EV), which, in retrospect, seems like a poor acquisition. Vidrala later sold it for the symbolic price of €1, booking an impairment of €11m in 2019. Yet, capital allocation is much more than buying well. While this acquisition may have turned out sour, the decision to sell it allows us to have a glimpse of Vidrala’s capital allocation when it comes to difficult decisions. Its Belgium plant suffered from structural difficulties as a consequence of the high labor costs, small scale and poor commercial positioning. All this resulted in low profitability margins and low ROIC at the plant level. Moreover, the plant operated two furnaces that were approaching their end of useful life in 2020-21, requiring at least €50m to maintain the same installed capacity. Although it seemed like a failure from the outside, the exit of Belgium was a disciplined capex allocation decision. The divestment freed up capital that would be better used towards regions in which Vidrala is especially competitive (namely, UK and Iberia).

In 2015, Vidrala makes its biggest acquisition ever by purchasing Encirc for €409m (EV). This allows Vidrala to expand its glass production capacity by ~70%. Encirc was originally controlled by Seán Quinn, which Forbes named the richest person in Ireland in 2008. As it happens, the financial crisis led to the Quinn empire’s bankruptcy in 2011 (it owed over €2.8bn just to one bank) and Vidrala bought Encirc from Quinn’s creditors. Encirc has the sole glass packaging plant in Ireland (built in ‘98) and one factory in England which is the largest glass packaging plant in Europe (built in 2005). The later also includes filling and logistics facilities — I will explain why this is important when reviewing The Park acquisition.

In 2017, Vidrala buys Santos Barosa Vidros, SBV, a company with a massive plant in Portugal with an annual production of 400 kTon, for €253m. At the time, SBV was led by the great-grandson of one of its founders. José Pedro Barosa, who went from being an academic professor to overseing the biggest glass packaging producer in the country. The year was 1988, and José was faced with a dilemma after a family tragedy. He was an economist with a promising academic career at the Nova Business School but, with his father's death in a tragic car accident, he decided to take over the family business. He certainly did a fantastic job over the following 29 years as SBV became one of the most productive and well operated plants in the world.

In 2022, Vidrada spent GBP 30m to acquire the bottling facilities operated by Accolade Wines in the UK, known as The Park. Vidrala has already filling facilities in its Encirc plant in the UK and owning The Park will allow for maximizing run lengths & efficiency of both plants. With its Encirc experience, Vidrala has noticed that clients value the “360 offering” in the UK where there is no wine production to speak of. UK imports mostly medium-to-low quality wine from remote regions (Australia, Chile, South Africa, California) and there are significant logistical savings for the client by shipping wine in bulk and bottling it in the UK. As previously mentioned, this would not be possible in Iberia or Italy: The wine produced here is mostly from DOC regions which demands that the wine is produced and bottled within the region.

And, finally, already in 2023, Vidrala agreed to acquire 29% of the third biggest independent player in Brazil, Vidroporto, for R$ 297m (or €53m). Vidrala’s goal is to acquire the full company — EV of about €300m — but that is pending the conclusion of litigation involving the seller. The owner of the remaining stake, the investment vehicle of the Salzano family “Quatroefe”, had an agreement to sell to another buyer, which expired without the transaction being closed. This potential buyer is now litigating the termination of the aforementioned contract. Vidroporto’s corporate history is also very interesting but I will save it for Part 2.

From an annual production of 450 kTon in 2003, Vidrala is now producing ~2,300 kTon, with much of this capacity added through acquisitions. The following table summarizes Vidrala’s M&A over the last 2 decades:

Verallia: Main Vidrala’s competitor

#1 in Europe, #2 LatAm, #3 Globally

It was part of Saint-Gobain until 2015 when it was sold to Apollo for an EV of €3bn. Apollo leveraged it up (increasing net debt from €0.4bn to €2bn) and IPOed it in 2017. Nowadays it no longer has a stake in Verallia and the main reference shareholder is BWSA (28%), an investment vehicle of the Brazilian family Moreira Salles.

Verallia is a well-operated company with significant overlapping exposure in Europe with Vidrala. It is also present in LatAm with plants in Brazil, Chile and Argentina, where it is rapidly growing with high EBITDA margins albeit still from a small base. Since Apollo’s leveraged buyout (LBO), Verallia has been able to successfully improve its profitability and has been significantly deleveraging its balance sheet towards conservative levels.

Recent M&A: Verallia bought Allied Glass (UK) for an EV of GBP 315m in November 2022

Allied Glass (now renamed Verallia UK) is the #4 player in the UK with ~10% of installed capacity (#1 is O-I, #2 Argardh & #3 Encirc, which belongs to Vidrala); Allied is focused on the premium segment where it has a ~30% market share.

OI Glass (OI): #2 in Europe, #1 LatAm, #1 Globally

Capital allocation has been subpar as OI was a very aggressive acquirer up until 2008. Take another look at the 1990 market shares on the chart above, of those major companies OI has acquired two: BSN (EV of €1.2bn, 2004) and Avir ($580m, 1997).

But more recently, OI has been in deleveraging mode. It sold its Australian & New Zealand business ($677m in 2020) and some miscellaneous assets ($221m in 2021/22) and did sales & leaseback (SLB) transactions. These SLB transactions, in particular, seem to be financial engineering to “artificially” reduce leverage. While OI did receive $371m in proceeds in 2022, it also agreed to pay an annual rent of $14.5m (increasing to $19m in 10 years) — basically equal to paying an interest rate of 4-5%. Despite these deleveraging efforts, it is still somewhat indebted.

OI also seems to be underinvesting (much lower capex as % of sales than peers), which is most likely unsustainable in the long-run.

Ardagh: Company in Dire Straits, #3 in Europe (#4 in Western Europe), #2 Globally

Ardagh is present in Europe, the Americas and Africa. Unlike the others in this list, it also produces metal containers.

“Money for nothing”: Ardagh has expanded through a series of acquisitions since Mr. Coulson, one of Ireland’s wealthiest, acquired an initial stake in the company in 1998. Ardagh first took over Britain’s largest glass bottle producer, Rockware, followed by a string of deals that saw Ardagh expand from the UK into mainland Europe and the Americas. Among many others, Ardagh has acquired Verallia’s US operations for $1.2bn (EV) in 2014. It went from being a local glass producer to a global giant both in glass and metal packaging — and it was all mostly financed with debt. A lot of it. With net debt of $8.6bn standing at >6x EBITDA, I believe that Ardagh will have to address its high leverage sooner rather than later. Perhaps some interesting assets will be for grabs as debt gets more difficult to serve.

“Your Latest Trick” (last Dire Straits reference, I promise) & a SPACtacular transaction: In 2021, Ardagh listed its metal packaging division via a SPAC while maintaining a controlling position (80%) on the resulting entity (uncreatively named Ardagh Metal Packaging, AMP) - in practice, it sold 20% of this division for ~$1bn in cash while spending a mind-blowing $415m (!) in transaction related costs. Ardagh then used part of its AMP shares as currency to buy-out its minority shareholders and take itself private.

The list of “exceptional” items that Ardagh highlights is worth nothing. The sheer amount of them might be the only truly exceptional part.

BA Glass: #5 in Europe, a very relevant player in Iberia

BA Glass is a Portuguese company with >50% of its sales coming from Iberia, while the remaining revenues come from other parts of Europe. Unlike OI and Ardagh, its capital allocation decisions have proven to be great ones. BA’s recent history is intimately connected to Carlos Moreira da Silva, BA’s former CEO that took ownership control of the company (together with the Moreira da Silva family) through a management buy-out (MBO) by acquiring the shares belonging to the Sonae group. If this rings a bell it is because BA is the 2nd Portuguese company I mentioned in Staying Rational with MBO and Sonae involved (the other being Ibersol in my previous write-up).

BA Glass has grown organically and through acquisitions in Spain, Poland and Germany. In 2017, BA made its biggest purchase yet: €500m (EV) to acquire the glass packaging businesses of Yioula Glass in Greece, Romania and Bulgaria. On a strike of wisdom or luck (or both), Yioula’s Ukranian plants have been excluded from the deal.

A significant part of BA’s plans are in low cost countries, such as Romania and Bulgaria and to a less extent Portugal and Spain. This has allowed BA to have best in class EBITDA margins of >30% in 2019-20. However, higher energy costs had a significant impact on BA’s profitability already in 2021. And while BA figures for 2022 have not yet been disclosed, I suspect that energy prices might have had a more severe impact on BA than on its peers due to the location of some of its production sites (higher exposure to Eastern Europe).

A boring industry with stable secular demand. All in all, the glass packaging industry is interesting to me for the reason it is also boring: it’s stable and predictable. It has also unique competitive dynamics that have allowed Vidrala, Verallia and BA to create significant value for their shareholders over the last few decades.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this write-up stay put for my next one where I will dive deeper on Vidrala’s fundamentals and valuation.

muito bom artigo e parabens pelo teu trabalho, um dia destes gostaria de trocar umas bolas contigo para ter algumas dicas para aprofundar mais estes temas. Já agora estou a sentir falta do podcast ascoes & CO

Thank you Gonzalo for this (and the next post): an excellent insight into a sector that has never excited minds but for that very reason can be an excellent investment opportunity. Interesting to see if opportunities may arise for excess OI debt